Beta Israel

One of the most ancient Jewish communities is the Beta Israel of Ethiopia. While there is little documentary evidence on their early history, legends and traditions indicate that the Beta Israel came to the Kingdom of Aksum and the Ethiopian Empire, before the destruction of the Second Temple in Jerusalem and the introduction of the Mishna and the Talmud. Judaism was widespread in the region, and the Beta Israel maintained the scriptures and customs of ancient biblical Israel. The existence of Ethiopian Jewry was made known to the outside world as early as the 9th century, when the Jewish traveler Eldad ha-Dani claimed that the Beta Israel descended from the tribe of Dan.

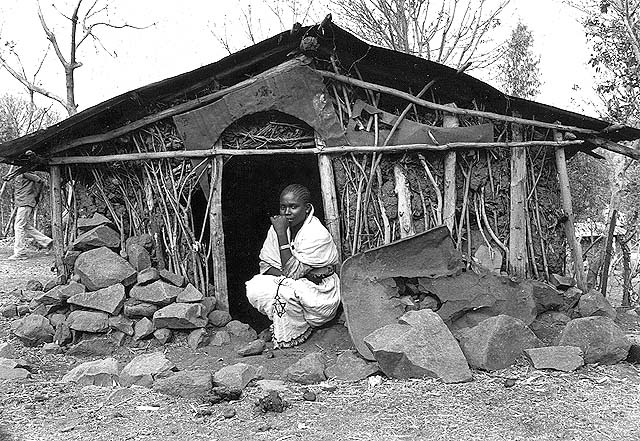

In the 4th century, the Aksum Kingdom converted to Christianity. Ethiopian Christianity was based on the heritage of the Hebrew bible and on the belief that the Christians were descendants of ancient Israeli nobility, specifically, of King Solomon. They therefore saw Ethiopia as the true Zion. Christians eventually came to dominate the country, and ultimately denounced the Jews for not accepting Jesus. Those remaining faithful to Judaism were persecuted and retreated to the mountains north of Lake Tana, in the province of Gondar. Because there were many similarities between the Judaism and Christianity practiced in Ethiopia, including Sabbath observance and similar dietary, circumcision, mourning rituals, it was easy, even tempting for Jews to convert to this denomination of Christianity in order to leave their rural areas and integrate with the country’s dominant groups. Nonetheless, many of the Beta Israel remained loyal to Judaism and, for centuries, yearned to return to Jerusalem.

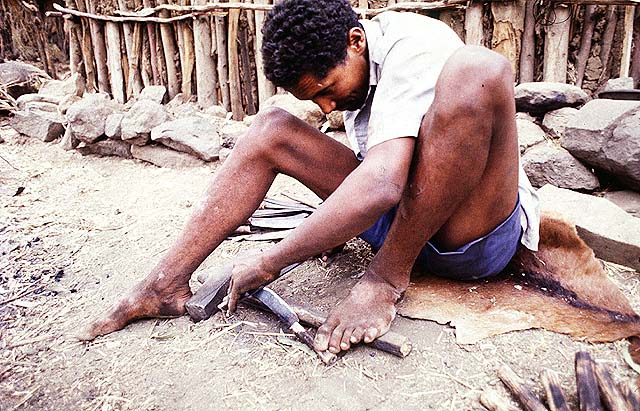

Preserving the ancient biblical customs of the Five Books of Moses in their remote villages, the Beta Israel observed some religious customs that were unique to their community. For example, they adhered to their own special purity laws, but they did not celebrate the tradition of Bar Mitzva or many of the non-biblical holidays, such as Purim or Hanukkah. Living in very remote areas, they were isolated from the greater Jewish world and were not aware of the introduction of Rabbinical and Talmudic laws. Only towards the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century, when travel opened up to the secluded areas where the Beta Israel lived, did deeper ties develop between the Beta Israel and the rest of the Jewish world. The relationship was not a smooth one, as much of the orthodox Jewish world did not accept the Jewishness of the Beta Israel. Still, there were many others, among them pioneers such as Prof. Jacques Faitlovitch and Yona Bogale, who worked to build an ongoing relationship between Ethiopian and world Jewry, increasing the world’s interest in the Beta Israel and their plight in Ethiopia.

The emerging State of Israel, facing existential challenges, built a strategic alliance with Emperor Haile Selassie. However, he was unwilling to accept the idea that any local community had the right to emigrate from the country, and the Beta Israel were forced to remain in Ethiopia. Only in the mid-1970s, thanks the heroic efforts of a new generation of Beta Israel and the State of Israel, Ethiopian Jewry was able to return to the promised land. The story of their Aliyah is too rich to be summarized here, but it is a story that must be recorded, told and retold.

עברית

עברית